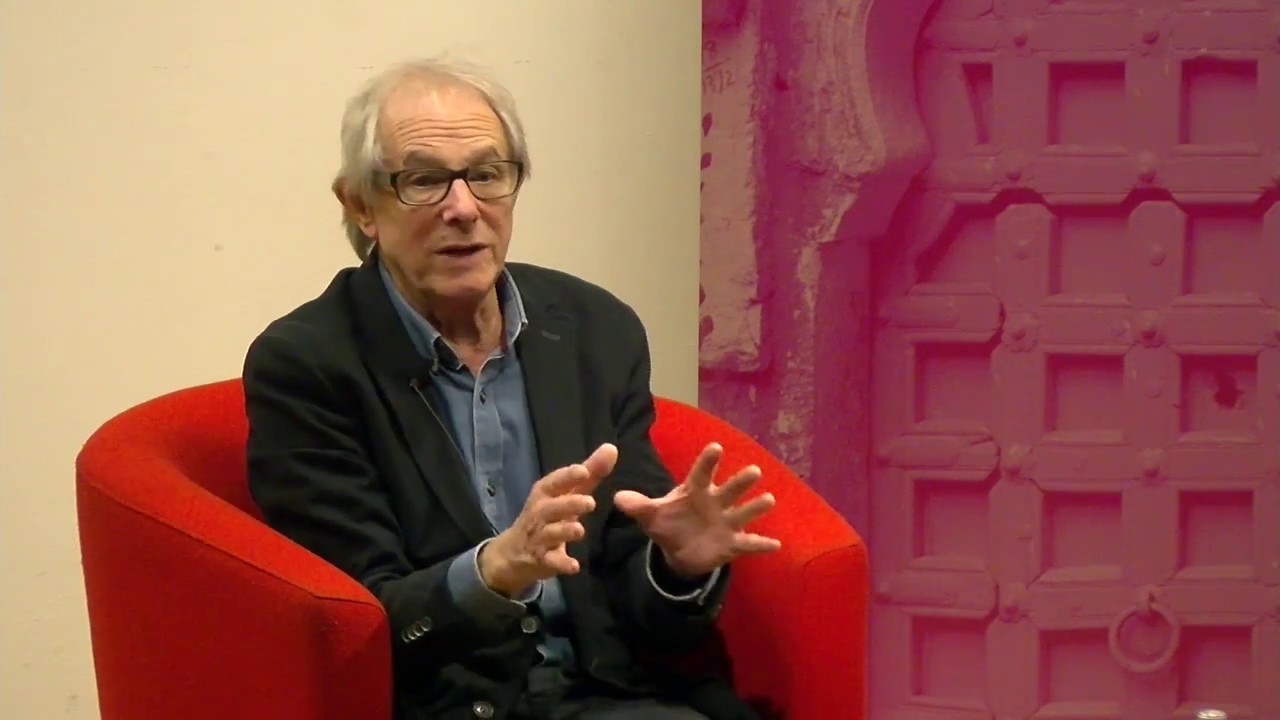

Ken Loach discusses austerity in neoliberal Britain

We don’t hear much about austerity in the mainstream media these days, and there was no mention of austerity in Philip Hammond’s latest Autumn Statement. But while homelessness, inequality and food banks continue to rise, the effects of austerity are only too real for growing numbers of people who can no longer make ends meet – those who fall between diminishing state protection and destitution.

These effects have specifically involved cuts to working-age welfare to the tune of £12 billion and increased sanctions for those who need benefits, and are movingly portrayed in Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake, which recently won the BAFTA for outstanding British film. The film is a testament to the power of political cinema at a time when standards of living in Britain are at their lowest since at least the 1980s, when in-work poverty is at record highs of 55% and when we face a government that is ideologically bent on making the poorest pay for the rapaciousness of bankers and the economic elite and the staggering short-termism of the political elite.

These are themes that Ken Loach picked up in the discussion following a screening of the film at SOAS last week, at which hundreds were present. Francesca Martinez, comedian, actor and writer, hosted the evening. Her questions were as penetrating as Loach’s answers. She argued that the capitalist system doesn’t know how to deal with people who have special health needs and different bodies – those who cannot be economic commodities – because if there is an acknowledgment that society should be caring and compassionate towards people with health issues, then it must follow that society should be caring and compassionate to everyone, something that is inimical to capitalism’s logic.

For Loach, the logic of profit and capitalist expansion leads to the great divide between the privileged few and those whose lives have descended into chaos, who continue to suffer at the hands of a bureaucracy that is not interested in helping people beyond survival, and who are told it’s their fault. This is neoliberalism at its worst: making people believe that not only is there no alternative, but that individuals themselves are to blame for being on the losing side of a bitterly hostile and fiercely competitive economic system. All in the name of meritocracy, freedom and progress.

Globally, neoliberalism has succeeded in the transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich through tax breaks for big business, privatisation on a grand scale, subsidies from the public purse to the private sector, across-the-board cuts to welfare, the proliferation of precarious employment, and a whole range of policies that have consolidated the privileges of the rich. But the restoration of profitability, which has been one of the central aims of the neoliberal project, has been mixed and governments are increasingly resorting to authoritarianism to push through economic imperatives, calling into question the legitimacy of neoliberalism itself.

For millions around the world, neoliberalism – in which austerity has been a recurring theme – is not working. It is increasingly being rejected at the level of electoral politics, where voters are shunning traditional candidates, and on the streets, where new movements are opposing traditional politics. This is being clearly expressed in the global anti-Trump protests asserting solidarity with migrants, women and black people, while opposing the new incarnation of privatising pro-corporate economics, this time with a protectionist spin.

Meanwhile, deeper questions over the economy and how the economic system is organised are beginning to emerge. When hunger is no longer a problem limited to the Global South and is increasing in Britain, one has to ask those who preside over the benefits system: ‘what is the crime for which hunger is the punishment?’ Loach says that I, Daniel Blake is about asking this very question. That the government has no answer reveals that austerity was never primarily about deficit reduction but rather reinforcing inequality: in 2013 for every £100 of deficit reduced, £85 came from spending cuts and £15 from increased taxes. On top of this, real wages are predicted to be no higher in 2021 than they were in 2007. These facts suggest that neoliberalism is unsustainable.

In a world where economic and political uncertainty is producing misery and increasing deprivation for those at the bottom of society, Loach has another question for us – one that he returned to at the BAFTAs – which side are you on?

- SOAS Radio interviewed Ken after the event.

The night was organised by the Department of Development Studies in conjunction with the People’s Assembly Against Austerity. This was a unique collaboration with the Department: the People’s Assembly is a broad-based campaigning group founded in 2013 that has put the defence of the NHS, support for migrants and refugees and trade unionism at the heart of the anti-austerity movement in Britain.