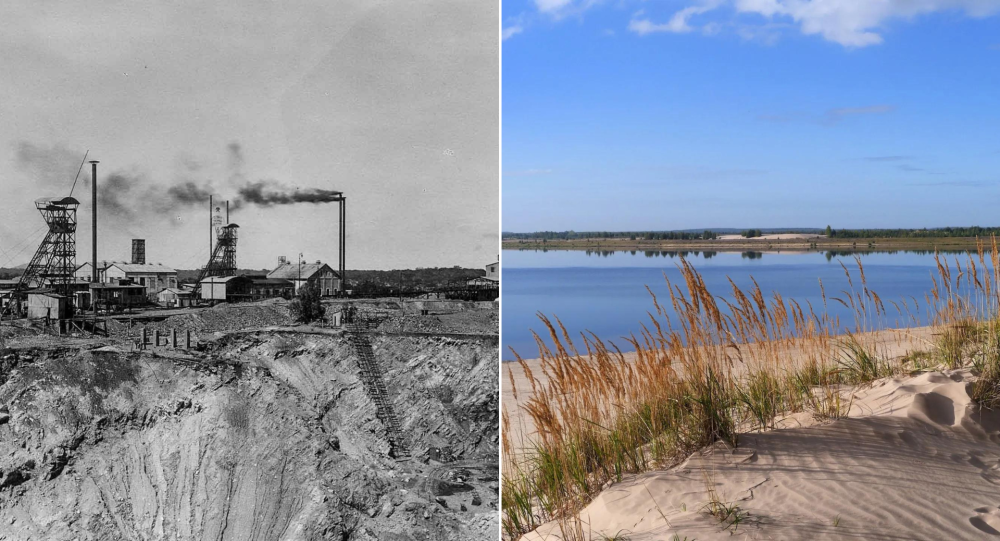

A tale of two mines connected by legacies of imperialism

MA student Nina Gribling contrasts the post-mining landscapes of the Lausitz region in Germany and the Tsumeb mine in Namibia, highlighting the social and environmental injustices from imperial legacy.?

Tale one

Imagine a dozen lakes stretching out across a vast landscape. What used to be one of Germany’s largest open-cast mining areas has been transformed into a ‘nature paradise’. Since the last mines closed, the Lausitzer mining company has ‘recultivated’ the scarred landscape through the creation of artificial lakes and forests. Attracting tourism and innovation, the company works together with local communities for a fossil-free future that is ‘secure, sustainable and livable’.

Tale two

Now, imagine another defunct mine located in a different place and time. Exploited under the German colonial regime for its copper, silver, lead and gold, the Tsumeb mine in Namibia has one of the richest mineral deposits worldwide. But with ore becoming less profitable, the mining company retreated in 1996. It left a large hole in the ground, as well as an abandoned town that now lives with the contaminated debris and is affected by the toxic fumes of a still-operating copper smelter.

The distribution of debris

In telling the stories of two mines, separated from each other by time and space and yet connected by legacies of imperialism, I take up Gabrielle Hecht’s invitation “to move across scalar registers” in our narratives of the Anthropocene. While the German transformation suggests a tale of progress that enables renewed inhabitation until far into the future, the end of development in Tsumeb only seems to suggest loss. After being inactive for two decades, what remains of both mines differs drastically, exposing the “coevalness (…) that allows modernity to thrive in some places at the (dialectical) expense of others”. However, stories of ‘progress’ and ‘loss’, Anna Tsing reminds us, are never as simple.

"While the German transformation suggests a tale of progress that enables renewed inhabitation until far into the future, the end of development in Tsumeb only seems to suggest loss."

Although the Lausitzer company aims to recover contaminated soil, it also covers up the damage inflicted upon people and the environment throughout decades of industrial activity. Recultivation logics, based on modern ontologies that separate ‘self’ from ‘other’ and ‘nature’ from ‘culture’, sustain the fantasy that contamination can be contained or displaced. Yet techno-fixes cannot fully mask the fact that environmental degradation remains active and creeps into bodies and souls long after industries close. A petro-ghost haunts the lakes of Lausitz, reminding of the 137 villages that made way for mines and of extraction taking place out of sight.

If Germany’s green transition depends on technological solutions in the form of artificial lakes, exemplifying what Dina Rajak refers to as a ‘deus ex machina’, it also depends on materials like copper extracted from more marginal places. Lying dormant, the future of Tsumeb is suspended, depending on whose vested interests might swing it back into the global flows of capitalism. With the installation Tsumeb Fragments, currently on display at the Barbican, artist Otobong Nkanga calls attention to the invisible but ongoing connections between places and bodies. Through her arrangement of Tsumeb’s debris, images and performances, Nkanga claims the forgotten mine as a monument to colonialism and exploitation in Namibia.

The examples illustrate how imperial legacies shape what means people have “to deal with what remains” to attend more closely to the ways mining debris is being reappropriated and (dis)regarded in the present, as argued by Ann Laura Stoler. A narrow focus on recultivation renders energy transitions technical, thereby obscuring social and environmental injustices while enabling extractive corporations to rebrand themselves as ‘responsible’ and ‘sustainable’.

Header image: Ivan Bandura via Unsplash.

About the author

Nina Gribling is a student of MA Anthropology of Global Futures and Sustainability (AY23-24) and has a background in Heritage and Urban Studies.