Woman, life, freedom: How a fight for women’s rights is uniting a nation

It is mid-September, and Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old student, walks on the streets of Iran’s capital Tehran surrounded by her family. Suddenly armed men and women - known as the morality police - stop her. An improper use of Hijab (some strands of hair being visible) and her skinny jeans ignite accusations against her inappropriate behaviour. She is taken by the morality squad in one of their notorious white Toyotas. She must be afraid, mulling over her day and choices and wondering how an outfit she would have picked in normal circumstances could dictate her arrest. She certainly accuses herself of bringing this unfortunate situation upon her. What she is unaware of is that she will die of a heart attack in just two days following her arrest. While official sources claim her heart failure came as a result of pre-existing health conditions, her family thinks otherwise. Her death was caused by excessive beating and violence used by the police meant to uphold principles of social virtue.

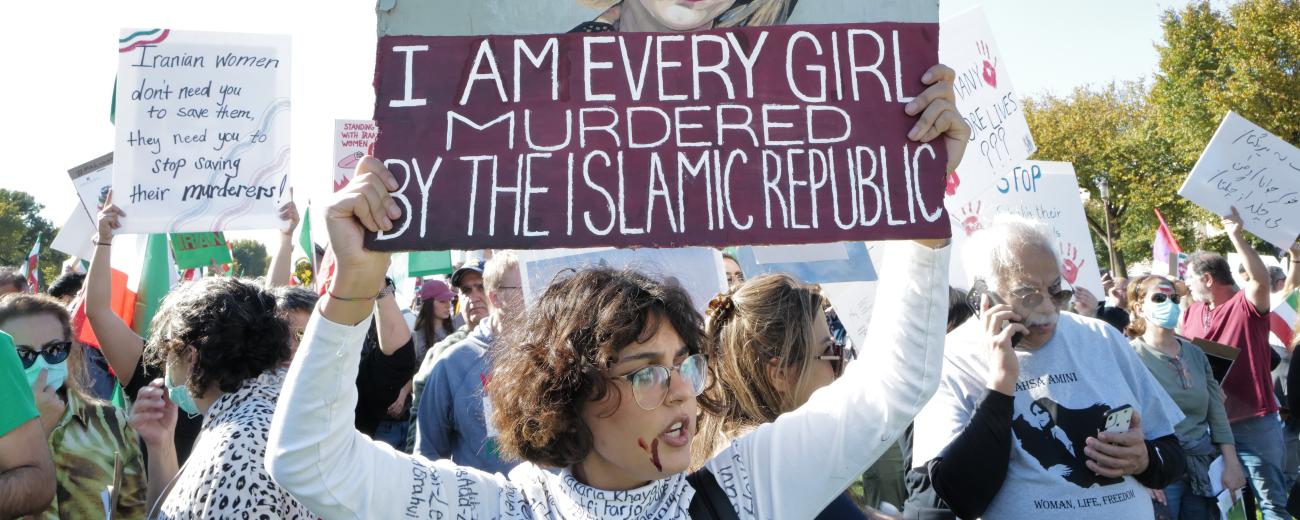

The echo of Mahsa's killing very soon reaches young students, mostly female, who begin to informally gather united by a chant encapsulating the vision for change in modern Iran: ‘Women, Life, Freedom’

- Woman, to defy decades of oppression, abuse, and violation of the most basic human rights

- Life, the fight for a life where women have a right to forge their own paths without theocratic restrictions

- Freedom, a concept so abstract yet so real to stir an entire nation - men and women - to die for it

Iran is not new to revolutions. Modern Iran’s most relevant political shifts originated through strong and violent ideological changes leading to complete systemic overhauls. Only 40 years ago, as discontent with the Shah grew, the Iranian newspaper, Ettela’at, sparked dissident sentiments amongst opposers of the monarchy and supporters of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. In 1978, security forces began attacking and killing protesters. This first event set Iran on a trail of demonstrations culminating with rebels ousting the Shah. The event marked the victory of the 1979 Islamic revolution. Khomeini, as one of the leaders of the revolt, took leadership of the new government following a referendum.

The theocracy introduced strict codes modelled on Shariah law and enforced by the morality police. Some of these laws included the control of media, strict sex segregation, and, most remarkably, the restriction of women’s clothing in public. Under the Islamic Republic, women had a choice to either wear a chador or a long robe and scarf. The uniqueness of this ‘new normal’ lied in the notion that women’s lives became a state affair. The government assumed legitimacy in governing women’s private sphere, denying them the right to their bodily autonomy and the right to choose.

In her book ‘Reading Lolita in Tehran,’ Azar Nafisi recounts of the stifling censorship of personal and artistic expression. Women, including herself, went from having professional careers, being accustomed to speaking their minds - especially against the backdrop of Iran’s tumultuous political history- to resign to a reality where supporters of the regime weaponised modesty as a virtue that separated Iran from the evils and moral corruption of the west. Nafisi describes the restrictions of women’s clothing as an almost out-of-body experience.

She writes: Now that I could not call myself a teacher, writer, now that I could not wear what I would normally wear, walk on the streets to the beat of my own body, shout if I wanted to or pat a male colleague on the back on the spur of the moment, now that all this was illegal, I felt light and fictional, as if I were walking on air as if I had been written into being and then erased in one quick swipe.

The repressive enforcement of these new rules did not only result in the physical death of unfortunate dissidents but also led to the spiritual demise of women who found themselves becoming tools of political propaganda. Women became more than their bodies, as leadership strategically idealised them into an abstract symbol of the Republic’s new principles. Their control carried a lot of weight as it signalled women’s buy-in into the theocracy and indirectly defined their value within this new world order. Their adherence to these new codes became directly proportional to the power and influence the regime could exert on its own people - and internationally - as they all came as a united ideological and political front.

For 43 years, keeping women veiled has been one of the most defining symbols of the republic – Ruhollah Khomeini once called it ‘the flag of the revolution’. Clerics have reckoned that its dismissal would herald the collapse of the theocracy. Women’s defiant act of burning their veils, therefore, carries a much deeper symbolic meaning than one would recognise if we were to understand the revolt at face value. Refusing this imposition openly rejects the totalitarian nature of a regime that, for too long, has enforced monolithic and out-of-touch theocratic principles on people hungry for social change. If the revolt was initially spearheaded by women, the protest’s universal message has, for the very first time, resonated with Iranians of all ages, ethnicities, and genders. Women were the first to take the streets, but soon after, as a reaction to the abuse they faced, men joined them to fight for a new Iran. “For dancing in the alley”, “For being afraid of kissing one another”, For yearning for a normal life.” chants the song “Baraye”. The lyrics give away some of the reasons young Iranians are fighting for.

What differentiates this protest from previous upheavals is the striking tenacity of its supporters in demanding an overthrow of the theocracy. Iranians are teaching the world about the power that lies in the commotion of young people. They are testimonies of how a repressed yearning for freedom can be channelled into a resilient civil movement that, despite a leadership hiatus, has spoken to different sects and ethnicities. Even after hundreds of deaths and thousands of arrests, Iran’s forces have failed to suppress the revolt. “We’re not a movement anymore,” a student at a university in Tehran declares. “We’re a revolution that’s giving birth to a nation.”

About the author

Alumna Chiara Laura Zin is an international development professional passionate about gender equality & empowerment issues. Chiara has pursued projects in the MENA region, Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and Latin America, with thematic areas covering refugee integration, tech for growth, international trade and green growth.