Why clientelistic politics matter for development prospects

Dr Miguel Niño-Zarazúa explores the complex effects of clientelism on economic development, state capacity, and governance, emphasising the need for nuanced research to understand these dynamics in the context of rising populism and autocracies.

The intricate relationship between clientelistic politics and economic development has long been a focal point of political science, economics and development research. However, with the rise of populism and autocracies across the world, it is imperative to better understand how clientelism may weaken state institutions and affect the checks and balances that hold political regimes accountable.

In a recent special issue in World Development, edited jointly with my colleagues Rachel M. Gisselquist and Kunal Sen, we delve into the multifaceted impacts of clientelism on economic development, state capacity, and state-society relations.

What is clientelism?

Clientelism is characterised by the exchange of private goods and services for political support. It often thrives in environments where political parties or leaders wield significant influence over voters through gifts and promises. Clientelism operates on an asymmetric power dynamic where politicians leverage their control over resources to secure votes, particularly targeting poorer segments of the electorate.

Clientelism operates on an asymmetric power dynamic where politicians leverage their control over resources to secure votes, particularly targeting poorer segments of the electorate.

This targeted exchange can have detrimental social impacts, including a weakened state capacity, inefficient allocation of public resources, and increased corruption. However, understanding the full extent of clientelism's impact requires exploring its mechanisms, consequences, and the contexts in which it succeeds.

Clientelism and poverty

The literature on clientelism often highlights its association with poverty. Politicians tend to focus on the poor, who are more susceptible to economic incentives due to the perceived benefits of clientelistic rewards. Studies have shown that poor voters, while strategic in their electoral decisions, often face coercion or feel bound by norms of reciprocity to comply with clientelistic exchanges.

Despite this, the relationship between patrons and clients remains bidirectional, compelling politicians to deliver on their promises to maintain credibility. Several contributing papers to the World Development special issue speak to these issues.

Nico Ravanilla and Allen Hicken, in their study on the Philippines, emphasise the role of social networks in determining which poor voters are targeted and the likelihood of their compliance. Similarly, Jorge Gallego, Jenny Guardado, and Leonard Wantchekon’s study across sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America reveals that vote-buying has a limited overall impact on electoral outcomes, challenging the conventional wisdom about its efficacy. In some cases, discretionary allocations of public resources may be more pro-poor than formula-based allocations as the study by Dilip Mookherjee and Anusha Nath in India has found.

Clientelism and state-society relations

Clientelism often circumvents formal rule-based governance, leading to poorer bureaucratic quality and reduced state capacity. Politicians may rely on political brokers who possess local knowledge to navigate voter preferences, but these brokers can act in self-interest, diverting resources away from their intended targets. The role of brokers and organisational intermediaries is a critical area for further research, particularly in understanding how these relationships evolve and influence state capacity.

Politicians may rely on political brokers who possess local knowledge to navigate voter preferences, but these brokers can act in self-interest, diverting resources away from their intended target.

Ana De La O's study on Mexico highlights how clientelism can trap local governments in low-capacity bureaucratic equilibria, underscoring the need to enhance bureaucratic quality to combat clientelism. Staffan Lindberg, Maria Lo Bue, and Kunal Sen provide support for the link between clientelism and political corruption and a weaker rule of law based on a cross-country analysis of 134 countries over the period 1900-2018. Moreover, Pranab Bardhan reflects on the broader implications of clientelism on governance, suggesting that economic development can weaken the structures supporting clientelistic exchanges.

Clientelism, electoral politics and policy-making

Clientelism's influence extends beyond pre-election periods into the realm of policy-making, where elected officials may continue to employ clientelistic strategies. This co-existence of clientelism and programmatic policies complicates the political landscape, particularly in regions experiencing a rise in populist movements, as I have shown in the context of Mexico, in a joint paper with Dragan Filipovich and Alma Santillán Hernández. The persistence of clientelism in such contexts underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of its dynamics. Ken Opalo's examination of Kenya's Harambee Movement and the Constituency Development Fund illustrates why clientelism persists as a credible means of fulfilling campaign promises. Furthermore, Prisca Jöst and Ellen Lust’s study on electoral handouts in Kenya, Malawi, and Zambia reveals how social ties within communities influence voters' expectations of service provision post-election.

The studies in this special issue highlight the complex interplay between clientelism and development, calling for more nuanced research to better understand these dynamics. Future research should focus on the underlying mechanisms of discretionary allocations and the role of social networks in mediating clientelistic exchanges.

Understanding the multifaceted relationship between clientelism and development is crucial for formulating effective policies aimed at fostering inclusive development. This special issue catalyses ongoing research, encouraging scholars to delve deeper into the intricate linkages between clientelism, economic development, state-society relations, and electoral politics.

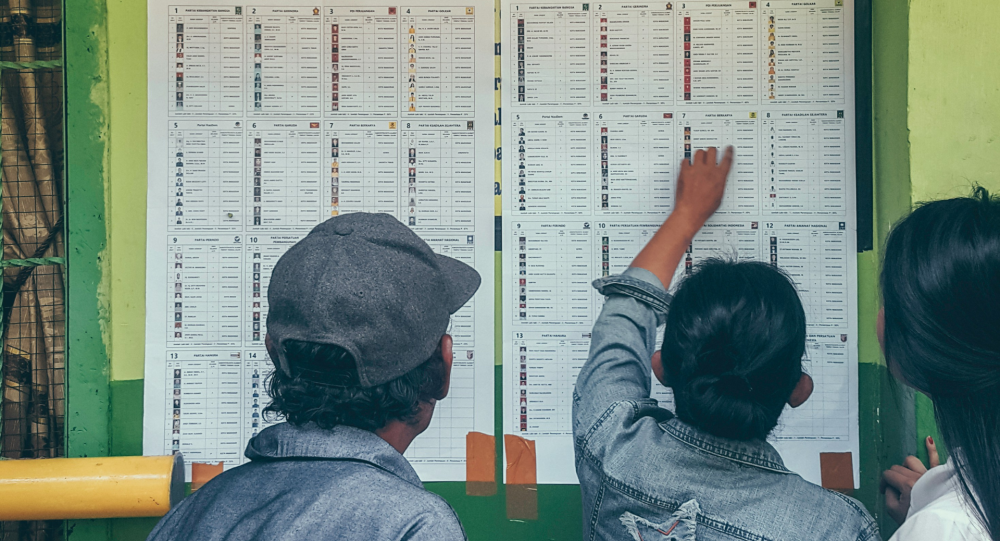

Header image credit: You Le via Unsplash

About the author

Dr Miguel Niño-Zarazúa is a Senior Lecturer in Development Economics at SOAS University of London and a Non-Resident Senior Research Fellow at the United Nations University-World Institute for Development Economics Research.