The story of SOAS

SOAS has many different stories and histories. This is a story of the people whose contributions changed SOAS – and the world beyond.

Foundation (1916–1929)

Royal Charter

SOAS was founded in 1916 as the School of Oriental Studies, a college of the University of London, and inaugurated the following year by George V, King of the British Dominions and Emperor of India. This was one of the few ceremonies he attended during the First World War, and its attendees – former viceroy of India Lord Curzon, and other government officials – make clear that this was an institution of unusual purpose.

This was, as the School’s Royal Charter puts it:

"...to give instruction in the Languages of Eastern and African peoples, Ancient and Modern, and in the Literature, History, Religion, and Customs of those peoples, especially with a view to the needs of persons about to proceed to the East or to Africa for the pursuit of study and research, commerce or a profession..."

An act of parliament enabled the School to occupy the London Institution building at Finsbury Circus, where it would be a centre of global scholarship, rivalling the famous "oriental" schools of Berlin, Paris and Saint Petersburg. But it would also train British colonial officials, providing knowledge of Britain's colonial subjects, their languages and cultures, so those officials could more effectively run an empire.

Small but distinguished

The School of Oriental Studies soon developed a reputation as a hotbed of spies and adventurers. William McGovern, a lecturer in Japanese at the School, made headlines in 1923 after smuggling himself into Lhasa in Tibet, having been denied access by its authorities (he is one of the possible inspirations for Indiana Jones). Freya Stark studied Arabic and Persian at the School in 1923, going on to explore and write about areas little known to Europeans, such as in The Valleys of the Assassins, about western Iran.

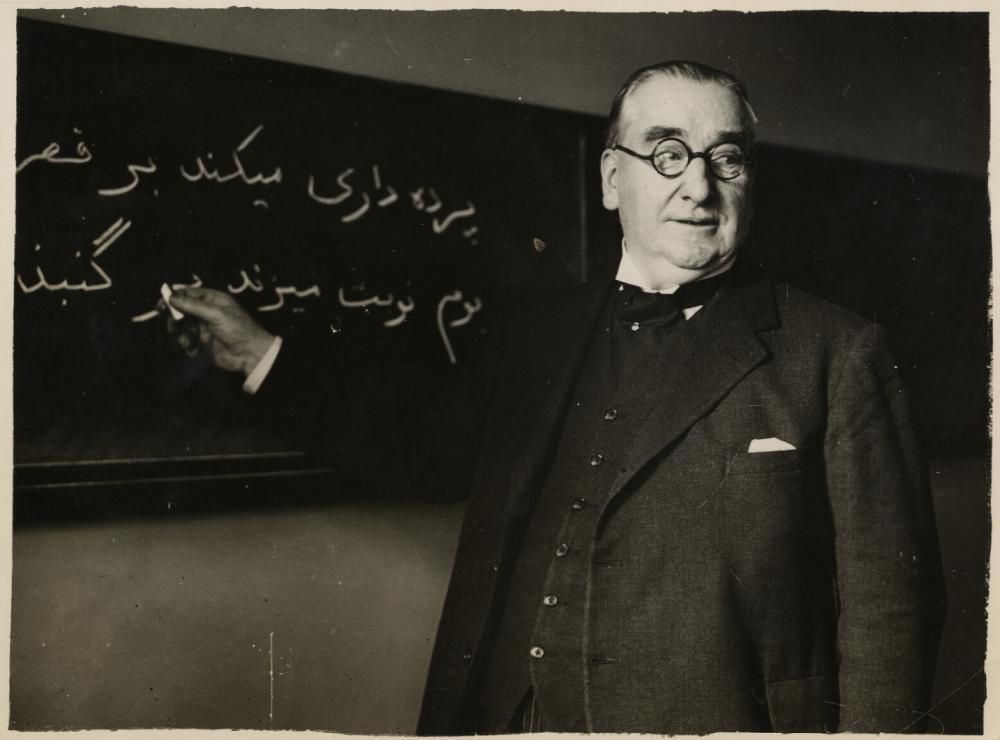

School’s first Director, Edward Denison Ross, had a background in imperial education as former Principal of the renowned Calcutta Madrasah. He spoke 12 languages and led a small but distinguished academic staff that included Bloomsbury Group writer and orientalist Arthur Waley, who translated and popularised important Chinese and Japanese poetry.

For the academics, the relationship between serving the British Empire and advancing knowledge of global peoples was complex. Many were committed to making people in Britain more aware of – and interested in – the societies and cultures that Britain ruled over. While Director, Ross wrote in The Times that acceptance of the term "Mohamedan" by the BBC Committee for Spoken English was wrong. "This expression is regarded by many Muslims as offensive on religious grounds," he said, "for it implies that they worship the Prophet, and the sooner it is expelled from everyday usage the better."

The early student population shows how the School soon reflected shifts in the empire and how it worked, particularly in terms of calls to devolve power in India. In the 1920-21 academic year, of the 274 men and 138 women enrolled, 54 were from India, among them Subbier Subramania Iyer, who would go on to become Vice-Chancellor of Lucknow University. That same year the first Doctor of Literature was awarded to Suniti Kumar Chatterji, who became a noted linguist and educationalist, and to the Bengali polymath Sushil Kumar De.

The racial diversity of the student body was echoed to a degree in the academic body, even at the School’s outset. This was diverse for a British institution of the period, but senior and permanent posts were predominantly held by those of white Western heritage.

Becoming SOAS (1930–1939)

Primary sources

From its foundation, the School led the field of linguistics in the UK. It did this by emphasising the importance of primary sources, written and spoken in the languages of the peoples studied, using these to understand their societies and cultural inheritance. The principle was established that the disciplines of a region would only be studied once its languages were understood.

This meant that, from the beginning, the study of people and places was seen as vital to the study of languages, and it triggered growth in many fields.

Chinese studies

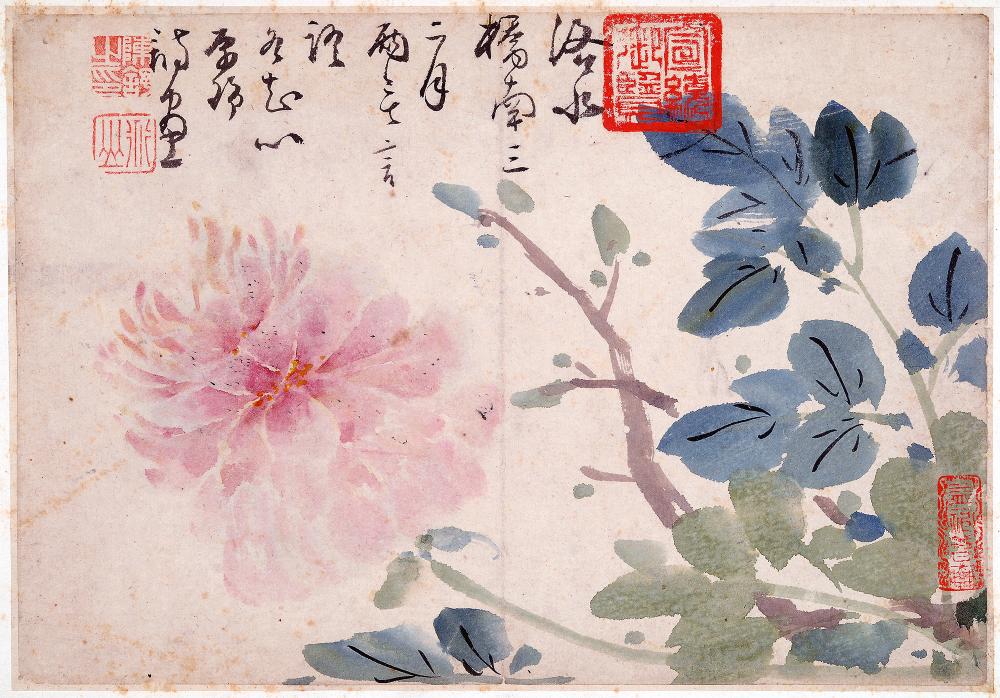

In the 19th century the University of London established the first professorship of Chinese, founding Chinese studies in the UK. This position passed to the School at its creation, and perhaps its most famous appointee was Reginald Johnston in 1931, having been English tutor to Puyi, the last emperor of China.

One of the first lecturers in Chinese literature was Evangeline Edwards, former Principal of a teacher training college in Mukden, China, and pioneer of the study of Tang fiction. She worked alongside the Beijing novelist Lao She, one of the greatest Chinese writers of the 20th century, who taught Mandarin at the school and was one of the first teachers of the language outside China.

The School’s Department of Linguistics was founded in 1932, the first in the UK, and the professorship of Chinese was awarded to Edwards in 1939, making her one of the first female professors in the UK.

The A in SOAS

At its founding, the School inherited a variety of existing posts in African and Asian languages from other University of London colleges. Figures like Alice Werner, who was central in developing the study of Swahili language and literature, especially in oral traditions, enabled the School to expand its research in African linguistics. This led to the launch of the African Linguistics and Phonetics Department in 1932.

Using a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, the department became world-leading, due in part to the efforts and personality of the phonetician Ida Ward. Known for her groundbreaking work in West African tonal languages, she was able to study many of these languages while at the School – including Efik, Igbo, Mende and Yoruba – because of the many African scholars and students there by the 1930s.

It was this environment that drew one of the School’s most illustrious alumni, the American bass-baritone singer, film actor and activist Paul Robeson. His studies of Swahili and phonetics coincided with a personal awakening in which he wrote his famous essay "I Want to be African".

In the essay he wrote:

"In my music, my plays, my films I want to carry always this central idea: to be African. Multitudes of men have died for less worthy ideals; it is even more eminently worth living for."

Ward became head of the Africa Department in 1937 and the following year the School changed its name: it was now the School of Oriental and African Studies. In the early 1940s it moved to buildings at Russell Square in Bloomsbury, where it stands today.

Wartime and post-war expansion (1940–1959)

Second World War

By the end of the 1930s, most of students taking language courses at the School were British cadets training for the Colonial Service and Indian Civil Service, as had been the case since its founding. But its degree students, while a small proportion of SOAS’s student body overall, were by this time largely from India – a situation unforeseen in 1916.

The outbreak of the Second World War saw the student population change quickly to military officers, the War Office having joined with the School to address the shortage of linguists in Japanese. Scholarships were offered to selected grammar and public school boys, who became known as the "Dulwich Boys", after their lodgings at Dulwich College.

Less well known is that a group of women was recruited to study Japanese to work in codebreaking at Bletchley Park. As well as this, large numbers of School staff worked in postal censorship, reading 32,000 letters between 1942 and 1945 – in 192 languages.

This did nothing to quell the old rumours that SOAS was full of spies. Nor did the reappearance of Freya Stark, over the road at the Ministry of Information, using her regional expertise to establish a propaganda network in North Africa.

But the war had increased public understanding of the importance of the School’s areas of study, and the need to find means of teaching Japanese in just six months had a major impact on language teaching methodologies, placing SOAS at the forefront of this. In diplomacy, the linguistic and cultural knowledge gained by the officers at SOAS formed the basis of a new post-war understanding between Japan and Britain.

The Scarborough Commission

The war set in motion other changes that would be important for the School’s academic mission. It retained its strong connection to empire (Enoch Powell came to study Urdu at SOAS in 1946 because he was convinced this training would enable him to become India's next viceroy) but few could ignore the fact that British imperialism had been put under strain by the war.

With the transfer of power in India, and changes in colonial government in African colonies, education and research about the world was seen as vital to maintain Britain’s global influence.

From this, the 1946 Scarborough Commission identified SOAS as the key academic centre nationally for its regions of study. Crucially, it recommended the expansion of Asian and African studies independently of undergraduate student demand. This brought funding for a major increase in teaching posts and subjects taught.

In this context, the study of South East Asia as a distinct region occurred first at SOAS, with the appointment of DGE Hall, a scholar of Burmese, in 1949. Meanwhile, Roland Oliver led SOAS historians in showing that there had been no academic study of African history, only the study of Europeans in Africa, and established African history as a distinct field of scholarship.

An emphasis of the Director, Cyril Philips, was that studies would embrace contemporary Asia, Africa and the Middle East, as opposed to the orientalist scholarship that had concerned only their pasts. In this context, cultural anthropologist Christoph von Furer-Haimendorf founded the Department of Cultural Anthropology, which he built into the largest anthropology department in Britain. Nonetheless, he is an example of the complexity and controversy that can surround such scholarship: his groundbreaking research on tribal communities was enabled through his connections with the colonial government of India.

Area studies and a world-class library (1960–1979)

The Hayter Committee

In 1961, as a spy was finally unmasked at SOAS (Soviet intelligence officer Konon Molody), the Hayter Committee recommended further expansion of British area studies.

SOAS scholars were first to formally study the People's Republic of China, founding the Contemporary China Institute and China Quarterly. Cyril Philips pioneered the radical field of area studies, which provided an interdisciplinary approach to teaching and research across the SOAS regions. Mary Boyce published the seminal History of Zoroastrianism, informed by fieldwork in Iran to study the faith as practised by both "priests and housewives". Jon Wansbrough and Michael Cooke caused controversy with new analysis of early Islamic history based on the only surviving contemporary accounts of the religion’s rise, manuscripts in Armenian, Greek, Aramaic and Syriac.

The School’s strength in social sciences continued to grow, reflecting its longstanding interdisciplinarity and use of varied, cutting-edge methods in studying its regions. In economics, Edith Penrose published her highly influential The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, and while Chair of Economics laid the foundations for SOAS research and teaching in economics, development studies, management and strategy.

Another of the School’s most famous alumni, Walter Rodney, undertook his PhD at this time while attending the weekly SOAS African History Seminar, founded by Roland Oliver and by then a key conduit for the advancement of African history globally. Rodney completed his thesis, titled A History of the Upper Guinea Coast 1545–1800, in 1966. He went on to write his landmark treatise How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and become an important radical intellectual, before his tragic assassination in 1980.

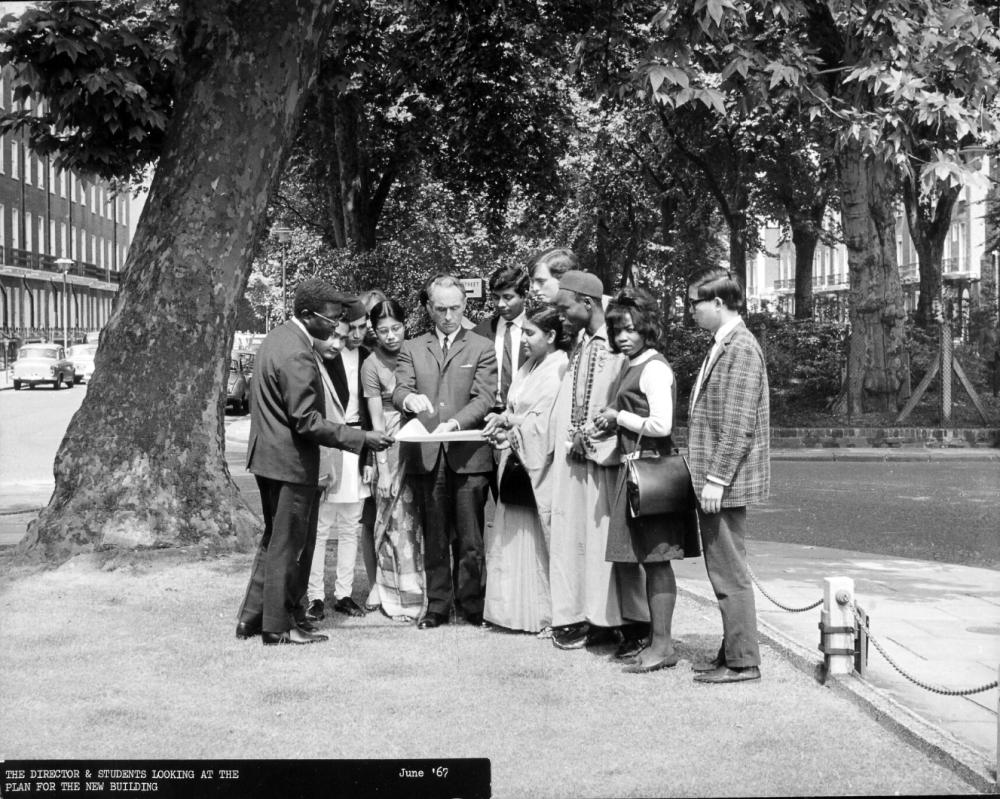

The Philips Building

By the 1970s the School had outgrown its premises and become scattered over several sites. Plans to transform Bloomsbury into a university precinct stretched back decades, but the time had come to make this part of Georgian London the central and permanent home of SOAS.

The centrepiece of the new campus would be a library appropriate to the international importance of its collections and to growing student numbers. Architect Denys Lasdun designed it in the "brutalist" style, after his nearby Institute of Education and the National Theatre on the South Bank.

The style was controversial. But, as with the National Theatre, the SOAS Library is now recognised as a classic. It was also ahead of its time in many ways: sitting at the base of its large, naturally lit atrium, the reading room is central to the design, anticipating how important these spaces would be to twenty-first-century university libraries. It opened in 1973.

Innovations ancient and modern (1980–present)

Subjects of national importance

Following lobbying from the School, a 1986 national enquiry led by Sir Peter Parker pointed to the severe losses suffered by Asian and African studies throughout the university system, and to the increasing demand from government and business for teaching and expertise relating to these regions. In 1993, the Raisman Committee advised the English university funding body that SOAS should receive an exceptional grant for specialist subjects of national importance.

Innovative scholarship continued. Historian Shula Marks challenged the liberal interpretation of South African history, leading an influential seminar series regularly attended by anti-apartheid activists Thabo Mbeke and Albie Sachs.

In studies of the ancient world, Andrew George made a first-hand translation of the cuneiform inscriptions on the clay tablets of Nineveh, producing the most definitive rendering of the 3,700-year-old Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh. Elizabeth Moore worked with NASA to analyse radar remote sensing data of Angkor Wat and other temple complexes in Cambodia. Collected by the space shuttle Endeavour, the imagery was compared with temple reliefs to document the distribution of phraa phum, or spirit posts, in the sites’ ancient hydrology.

The theme of water continues in the modern day, with Tony Allen publishing The Middle East Water Question: Hydropolitics and the Global Economy in 2000. His concept of "virtual water" has become a cornerstone for policy-makers and researchers across the globe, and water remains a vital part of SOAS research and teaching in development studies.

The Brunei Gallery and the Paul Webley Wing

Meanwhile, the Brunei Gallery – a unique resource among UK universities – had opened to promote the SOAS regions of Asia, Africa and the Middle East through a programme of changing exhibitions. It has since held over 250 exhibitions, from Pure Soul: The Jaina Spiritual Traditions to Japanese Aesthetics of Recycling. Originally featuring an Islamic-style water garden on its roof, this changed to a Japanese-inspired roof garden as part of Anglo-Japan celebrations in 2001.

In 2011 the SOAS Library was designated a National Research Library, one of only five in the UK, and in 2016 part of the historic Senate House building joined the SOAS campus as the Paul Webley Wing. The building once home to the Ministry of Information (and inspiration for George Orwell’s Ministry of Truth) now houses teaching rooms and a glass-covered atrium.

Academic research grew in depth and diversity over these years, aided by SOAS academics collaborating to establish new research centres within and beyond the School. Through these, SOAS engages with contemporary challenges of climate and globalisation, championing the rights of displaced people through research strengths in migration and diaspora, and developing the governance and management of water, minerals, energy and nutrition.

SOAS today

Unique insight

SOAS does not shy away from its origins as an institution of the British Empire, established to train colonial officials over a century ago. The SOAS of today is a dynamic and progressive place of many viewpoints, and would not be what it is without the journey it has taken.

There is no single moment on this journey when SOAS shifted from being a "colonial" to a "post-colonial" institution. But from the beginning it has been a place where students and academics have questioned, debated and fought about how to understand the regions of the world that were subjected to colonialism. Their diverse experiences have made it a place of unique insight.

The name itself has been at the core of this journey. Over recent years the students and staff have discussed the name, what it means to them and how it evokes our history, and the School now refers to itself as SOAS University of London. This reflects the changing nature of the institution without forgetting its foundations.

The World's University

Today, the School is a major contributor to the idea of "decolonising" organisations and curricula, and is innovating equitable global partnerships to build fair and co-owned initiatives between the School and partners across Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

SOAS graduates are diplomats, ambassadors and ministers to governments around the world, as well as artists, musicians and activists. Their range of skills and perspectives is unparalleled and grows by the year.

What they share – and SOAS shares with them – is a truly global outlook, and a desire to change the world for the better.