3 critical questions that shape classroom discussions

MA student Lilly reveals the critical questions posed in SOAS classrooms and why they are key in driving learning and discovery.

A friend of mine recently asked me what my favourite punctuation mark was. My first instinct was the em-dash—there’s nothing quite as climactic as a slash between thoughts. But upon further reflection, I realised which symbol truly defined my most recent syntax. The question mark.

What stands out most in my education so far is how the faculty encourages us to pose questions.

SOAS prides itself on addressing some of the world’s most pressing issues, from public health to international law. Yet what stands out most in my education so far is how the faculty encourages us to pose questions. Over this term, I’ve paid particular attention to the many question marks in the classroom; here are three that stand out as some of the most critical.

Who has the power to tell stories?

This question challenges us to consider not only who crafts narratives but also how these narratives are shaped and circulated. In our discussions, my peers and I examine the distinct ways in which marginalised voices have been controlled throughout history in comparison with the present.

Though methods of oppression today may, at times, be less conspicuous, they continue to silence subaltern perspectives.

In what ways has tradition transformed?

The globalization of the last few decades has connected the world virtually and economically, intertwining cultures and languages to the point that authenticity has become almost impossible to discern. What does it mean, my professors often ask, when customs and conventions converge? How might cultural hybridity challenge our understanding of identity?

How does someone belong?

“Home” is as much a nostalgic concept as it is a nebulous one—in reality, belonging today is defined by a host of forces, including borders, heritage, and language. Especially concerning migrants and refugees, my peers and I continuously confront who is included and who is excluded in community-making practices across the world.

Of course, SOAS students have answers to these questions—many answers. That is, at least in part, our task as emerging academics.

My discussions with my faculty and fellow peers, however, have taught me the significance of posing questions instead of simply offering solutions.

My discussions with my faculty and fellow peers, however, have taught me the significance of posing questions instead of simply offering solutions. At SOAS, I’ve learned the practice of questioning, the praxis of doubt that is sorely neglected in today’s discourse, whether within the institution or over the dinner table.

I wonder how academia and decision-making institutions might be transformed by prioritising the question mark over the period. I wonder: what changes when we ask instead of answer?

About the author

A.L. (Lilly) Clausen received an MFA in Writing from the University of San Francisco and a BA in International Political Economy from Sarah Lawrence College.

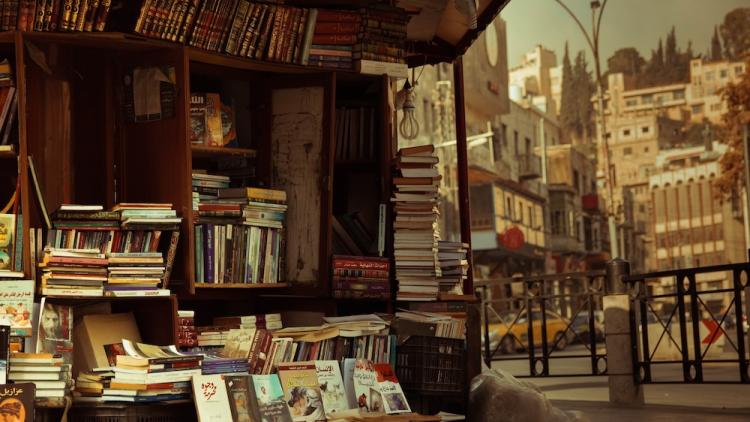

She is currently an MA candidate in Cultural Studies at SOAS, where she researches the publishing industry through the framework of late-stage capitalism. When she's not lost in a good book, Lilly loves to sing, tap, and craft stories on the page.