Introduction to Anthropology and Ethnography

Overview

As a discipline Anthropology focuses on the study of people and cultures, observing the nuances of daily life, practices and beliefs of different groups of people across the globe. Ethnography is the method through which this is achieved, the active observation and interaction with a particular section of humanity or society as an intentional act of research to collect data. As discipline and method the two are necessarily intertwined and aim at shedding light on human experience, ideally the untold stories that lie beyond popular narratives, assumptions and structures.

Anthropology has been defined as 'the science of humanity' (Encyclopaedia Britannica online, accessed 2021) and is a broad field spanning biology and evolutionary history to the study of society and culture. In academia it sits, sometimes awkwardly, at the intersection of the natural sciences and humanities and as such is often split into specialised fields; social anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and psychological anthropology for example. Archaeology and comparative philology were key methods of early anthropological studies (See EB Tylor, James George Frazer, Marcel Mauss). Whilst these studies provided interesting observations and categorisation they had a tendency towards grand universalising theories which were largely speculative and overlooked lived experiences and beliefs. In response, the 20th century saw a rise in the adoption and importance of fieldwork and the discipline of ethnography (See Bronislaw Malinowski).

Ethnography then is a method of study based on first-hand experience. Through field-work and (usually) a range of qualitative research methods, such as interviews, field notes and observation, an ethnographic study aims to understand the particular group of people. It places significance on their emic (insider) view, experience and understanding and then combines that with the etic (outsider) view and theoretical contextualisation of the researcher. Although ethnography was first championed as a method within anthropology, many disciplines now find value in this research approach - including Yoga Studies! Including ethnographic methods enables a researcher to layer fieldwork data into a study to validate broader theoretical arguments and hypothesis.

Within the field of Yoga Studies, the combined theory and method of Anthropology and Ethnography provides a two-tiered foundation to study practices and communities in different cultural, religious and social contexts. In this vein Mircea Eliade's Yoga, Immortality and Freedom (1969) a study of the development of the yoga tradition in India, is often cited as a pivotal work. However, although Eliade draws on his own experiences in India, he also falls prey to the universalising tendencies of the early anthropologists and appears to be unaware of his own biases and historical positioning (see Allen 2008).

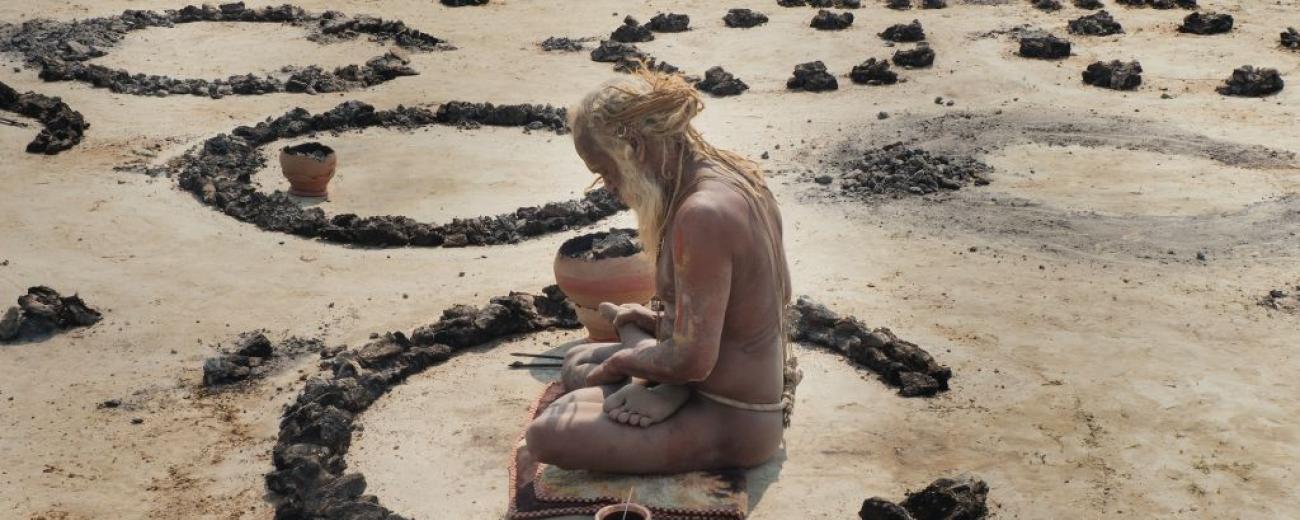

More recently, studies of modern yoga have benefited from interdisciplinary approaches that incorporate ethnographic methods (See Bevilacqua 2020). Indeed, the diversity of yoga's contemporary global and local landscapes provide ample source material for study and the opportunity to further our understanding of complex cultural exchange and knowledge transfer (Hauser 2013). For any researcher this exciting opportunity also comes with the need for attentive reflexivity; always retaining a self-awareness of what their own involvement is bringing to a study, alongside the honouring of participant experience, and the wider implications of these two viewpoints coming together.

[Image credit: Daniela Bevilacqua]

Audio Interview - Dr. Daniela Bevilacqua

Recommended reading

- Allen, D. (2008). ‘Prologue: Encounters with Mircea Eliade and his legacy for the 21st century.’ Religion 38(4): 319-327.

- Bevilacqua, Daniela (2017). ‘Are women entitled to become ascetics?: An historical and ethnographic glimpse on female asceticism in Hindu religions’, in International Journal of Afro-Asiatic Studies n. 21. Available at IJAAS.

- Bevilacqua, Daniela (2020). 'OBSERVING YOGA: The use of ethnography to develop yoga studies', in The Routledge Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies, edited by S Newcombe and K O 'Brien-Kop. Routledge.

- Lindahl, J. R., et al. (2017). ‘The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists.’ PLOS ONE 12(5). Available on open access at PLOS ONE.

[Interesting to read this article alongside the Pagis below to compare the different ethnographic approaches and conclusions.] - Cort, John E (2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press.

- Downey, Dalidowicz and Mason (2015). ‘Apprenticeship as method: embodied learning in ethnographic practice’, Qualitative Research, 2015, Vol. 15(2) 183–200

- Eliade, Mircea (1969). Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. New York: Princeton University Press.

- Hauser, Beatrix eds. (2013). Yoga Traveling: Bodily Practice in Transcultural Perspective. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Lamb, Ramdas (2005). Rāja Yoga, Asceticism, and the Rāmānanda Saṃpradāy, in Theory and Practice of Yoga: Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson, ed. Knut A Jacobsen. Brill. Available on Brill.com.

- Pagis, Michal (2010). ‘Producing Intersubjectivity in Silence: An Ethnographic Study of Meditation Practice.’ Ethnography, vol. 11, no. 2, Sage Publications, Ltd., 2010, pp. 309–28. Available on JSTOR.

- Singleton, M and Larios, B (2021). 'The Scholar-Practitioner of Yoga in the Western Academy' in The Routledge Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies, edited by Suzanne Newcombe and Karen O’Brien-Kop. Routledge.