Decolonising Bloomsbury: A guided walking tour through London’s colonial legacy

Dr Alia Amir, Research Associate at the School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, takes us on a 'decolonising walk' through Bloomsbury, London and reflects on some of the historical landmarks while challenging us to confront colonial histories and envision a more just future.

Decolonisation is not a passive endeavour; it is an active transformation involving unlearning and relearning new patterns. Colonisation prevails through the legacy of colonial policies and patterns and is concealed in various aspects of the societies, including the school curriculum.

Being consciously aware of the surroundings and acknowledging the legacies of the material world which ruled the colonies in our environments is important for deconstructing the role of the Empire and its continued violent impact on people around the world.

A ‘decolonising walk’ is a path to consciously embody, visualise, feel, touch, remember, and recall the remnants of the semiotics of the physical structures of the colonial era in our environments. Where else would one have a decolonial walk but in the centre of the former Empire - London, Bloomsbury and SOAS. Here are some of the stops along the way, you can follow along via the map.

SOAS University of London

One could not help but notice the irony prevailing here. Founded in 1916 as the 'School of Oriental Studies', the institution’s roots in the British Empire offer an interesting juxtaposition to the complexities of its present state.

The school was formed with an explicitly imperial purpose, primarily for the colonial administrators, government officials, military officers, and business folks who ran the British Empire in the languages of Asia and Africa. It was the UK centre for teaching and research on the cultures and languages of vast areas of the world in Britain’s imperialistic thrall. But they were not learning the languages of the empire to understand and develop amicable and mutually beneficial relationships with the people they were ruling, but to overpower and, in some cases, erase them.

Decolonisation is not a passive endeavour; it is an active transformation involving unlearning and relearning new patterns.

Quoting the remarks of the former US Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, in 1962, in the middle of the twentieth century, the School of Oriental and African Studies lost an empire but, unlike Great Britain, found a role.

The question I ask myself is what would decoloniality mean in the case of SOAS University of London, which, in fact, is not the original sin, but as an arm of the Empire created to learn the languages of the former colonies, could it contribute differently for repatriation purposes? SOAS, in its modern form, challenges and decolonises the curriculum in many ways as it is the only European university that not only focuses on Asia and Africa but also has one of the most diverse faculty in the United Kingdom.

Gordon Square

As we enter Gordon Square, we encounter the bust of Noor Inayat Khan, a British Indian spy who served Great Britain in France during WWII. It's noteworthy that Khan's lineage traces back to Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore, who fiercely resisted British rule and died in battle in 1799.

Khan's journey, from the descendant of a ruler who fought against British colonialism to becoming the first female radio operator sent into France in 1943, encapsulates the intricate layers of colonial history. By shifting our perspective away from the centre of imperial power and embracing a more inclusive approach to history, we gain insights into the complexities of colonial legacies. Through this lens, we can empower ourselves and contribute to addressing historical and systemic imbalances.

The Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Wing

Our next stop is the representative home and legacy of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman to qualify as a physician and surgeon in Britain, born in 1836. Despite societal limitations on women during her time, Anderson's father's business success enabled her education. Her groundbreaking achievements included co-founding a women-staffed hospital and becoming the first dean of a British medical school.

This prompts inquiries into the colonial influences on such milestones. How did the expanding empire and its economic gains impact gender roles? Despite the British Empire's global dominance, why did the integration of women into medicine lag behind?

While we now take rights like voting, education, and work for granted, they were denied during the British Empire's rule. Colonial power structures perpetuated women's oppression despite anti-colonial feminist movements in the Global South. Mainstream feminist movements, although instrumental in securing basic rights, often prioritise white feminism, perpetuating hierarchies.

Advocating for decolonial feminism becomes crucial. It requires looking beyond the notion of a universal woman and addressing the ways in which the social categories of gender, ability, age, race, sexuality, nationality, religion, and class reinforce one another to produce marginalised individuals.

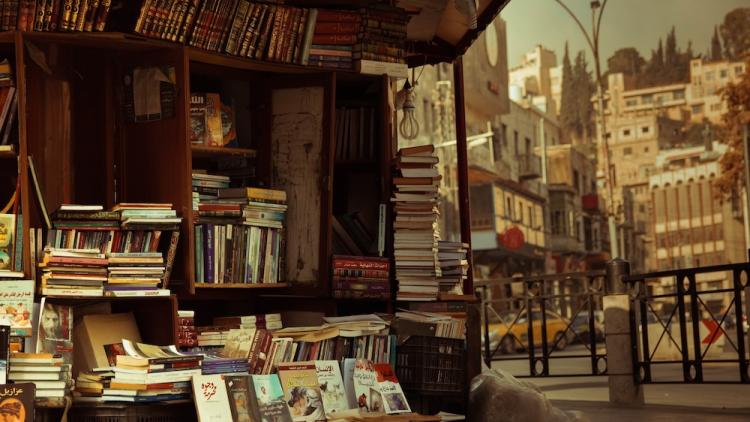

The British Museum

Next, we stop at the British Museum, which declares itself as a public museum dedicated to human history, art, and culture with a permanent collection of eight million items. While historically significant as the first public national museum covering diverse fields of knowledge, its name belies its true nature. In reality, the British Museum serves as a 'world museum,' acquiring artefacts globally and rooted in the expansion of the British Empire.

In reality, the British Museum serves as a 'world museum,' acquiring artefacts globally and rooted in the expansion of the British Empire.

Since its public opening in 1759, the British Museum's growth over 250 years was fueled by British colonisation, spawning branch institutions like the Natural History Museum in 1881. Despite acknowledging its foundations in the collections of Sir Hans Sloane, the museum's website falls short in critically examining the means of acquisition and their impact on indigenous communities.

Repatriating artefacts or compensating for damages, while ecologically sound, raises questions about addressing societal hierarchies and racial supremacy perpetuated by colonialism. While history cannot be undone, critical exploration of colonial artefacts and structures is imperative. The British Museum's silence on its acquisition processes obscures the broader impact of its collections on the world, underscoring the need for transparency and accountability in confronting colonial legacies.

The Wiener Holocaust Library

Moving on to our next destination, The Wiener Holocaust Library is one of the world’s leading and most extensive archives on the Holocaust, the Nazi era and genocide. In 2023, the library turned 90 and was the longest-running library with its unique collection of over 1 million items, including published and unpublished works, press cuttings, photographs, and eyewitness testimony.

The library reminds us of the importance of archives, even for difficult episodes in history. The question then arises is, while the Holocaust and antisemitism stand as the gravest mark on European history, what kind of memorials of the European colonisation outside of Europe are needed to remember the great injustices done to indigenous communities through annihilation and slavery?

While our discussion has primarily focused on British and European colonisation, it's essential to recognise that colonial violence and unequal epistemologies persist globally. Whether in Europe or abroad, the nature of colonial injustices prompts us to reflect on the broader implications of colonisation throughout history. Let us take inspiration from our ‘decolonial walk’ and, in a literal sense, be ‘the empire strikes back’ - in a more just way.

This blog was expanded from a walk hosted by Dr Alia Amir at the British Association of Applied Linguistics (BAAL) biannual Language Policy Forum 2023. SOAS also runs an MA Postcolonial Studies focusing on the historical relationships of power, domination and practices of imperialism and colonialism through the study of literature and culture.

About the author

Dr Alia Amir is a Research Associate at the School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics at SOAS University of London.