Entangled Pasts: Unraveling the interwoven histories of art and colonialism

MA students Sakshi Mavi and Saavani Karkhanis reflect on the exhibition 'Entangled Pasts, 1768–now: Art, Colonialism and Change' at the Royal Academy of Arts and how it explores the concepts of art, empire, power and resistance.

Art has the capacity to inform public discourse and evoke emotions and sympathy among the viewers. As students at SOAS, we visited The Royal Academy’s exhibition, ‘Entangled Pasts, 1768-now: Art, Colonialism and Change’ to discover how it tries to tackle the politics of Entanglement through a display of paintings, sculpture, and other mixed-media forms of expression.

The concept of entanglement

Entanglement is a curious word, evoking complex interconnections yet often lacking context about its own nature. The politics of entanglement are neither uniform nor free from social hierarchies.

As students of Area Studies at SOAS, our primary academic aim is to reimagine regions not as remnants of Cold War geographical categorisations but as interconnected cultural spaces. This exhibition captures the essence of intertwined histories between cultures historically seen as the ‘other.’

Art and orientalism: Tools of empire

Orientalism has been deeply studied by scholars for many decades now as not simply being militaristic in nature but employing cultural objects such as art and literature to maintain the Empire. Art has the capacity to inform public discourse and evoke emotions and sympathy among the viewers.

As students of Area Studies at SOAS, our primary academic aim is to reimagine regions not as remnants of Cold War geographical categorisations but as interconnected cultural spaces.

Colonised cultures are inherently imagined through art as being ‘different’ to the Occident, and this difference in aesthetics and ideals of beauty becomes stark in appropriations of oriental art, motifs and landscapes.

Juxtaposing narratives: Art as a site of power and resistance

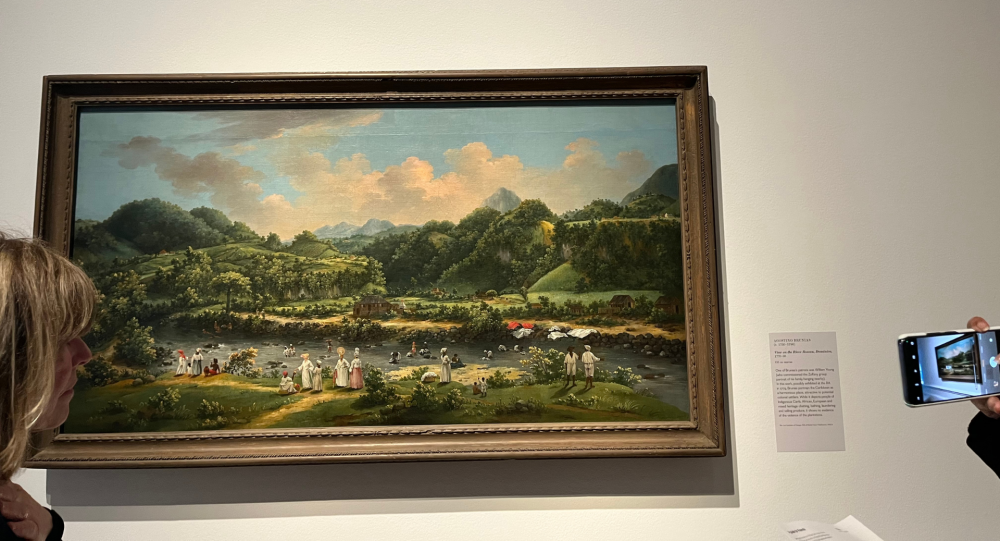

The exhibition sets the tone with a myriad of depictions of people of colour through the coloniser’s gaze over centuries. Art serves as a site for power, beauty, and difference, shaping and shifting narratives of the colonial project, resistance, abolition, and slavery.

The entanglement of colonial histories and the subjective experiences of the colonized form part of the decolonising project at SOAS. The institution critiques existing forms of knowledge derived from Western conceptions of the Oriental, much like the exhibition juxtaposes idealised representations of colonialism with recent artworks resisting such renditions.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the exhibition is the deliberate juxtaposition of parallel representations of people, compelling the audience to rethink the silencing and erasure of enslaved lives. For instance, Hew Locke’s Armada is placed amidst a room full of Royal Academy-sponsored paintings showcasing aristocratic European families and their fortunes. Exoticized ‘oriental’ landscapes are displayed alongside Karen McLean’s Primitive Matters: Huts installation, highlighting differences in wealth, status, and skin colour.

The sequencing of galleries is an unsettling journey

We could not help but comprehend the sequencing of galleries. First, a room filled with Renaissance-inspired paintings objectifying the black sitters and glorifying white colonial superiority by placing them at the peripheries of paintings, sometimes totally erasing their presence. Then, highlighting their presence but in racially stereotyped ways and their roles in the triangular slave trade, proceeding to the crisis of migration and loss of identity.

While one direction of this entanglement has been deeply explored, the gaze of the colonised towards the coloniser is curiously missing.

It then moves to the politics of racial difference and takes the audience on an unsettling journey across the Atlantic, evoking both remorse and respect for the enslaved victims. The last rooms uplift the mood, symbolizing the poignant presence of these people, having lost their identities but still retaining their culture and memories, resolute and determined to be remembered.

A missing perspective: the gaze of the colonised

What the exhibition leaves space for is how the Occident was then imagined by the Orient. While one direction of this entanglement has been deeply explored, the gaze of the colonised towards the coloniser is curiously missing. How did the colonised imagine the West? How did they interact with Western ideals of beauty? How does the art created within African and Asian cultures depict the difference between the coloniser and the colonised?

Perhaps these are questions left to be internally contemplated upon, or perhaps, like most studies of non-Western cultures, they are imagined to be the prerogative of formally colonised people. Whatever may be the case, it gives one much to think about, inviting viewers to reflect on the complex narratives of our shared past.

About the authors

Sakshi Mavi is a V.P Kanitkar Memorial scholar studying MA South Asian Area Studies at SOAS University of London. She is interested in the dynamics of memory, oral history and the politics of remembering, her research focusing on the gendered dimension of the 1947 Partition of India.

Sakshi is also interested in exploring the politics of performative representation in museums as a decolonisation practice and likes interpreting artworks, being an artist herself. She studied MA History at Lady Shri Ram College, University of Delhi.

Saavani Karkhanis is a postgraduate student of South Asian Area Studies at SOAS University of London. She did her bachelor’s in History from St. Stephen’s College, New Delhi. Her research interests lie in the cultural history of colonial South Asia and the questions of gender animating cultural space.

Saavani is particularly interested in notions of ‘agency’ and ‘negotiation’ within formerly colonised societies and how the colonised self is visualised through mediums of self-expression and interacts with a post-colonial, globalised world.