My internship at the SOAS Library: Curating a digital exhibition with a critical and decolonial lens

BA History student Sahaana recounts their SOAS Library internship, where they curated a digital exhibition. By digitizing South Asian artefacts through a decolonial lens, they showed how digital platforms can democratize access to history and challenge colonial narratives.

As a co-creator intern working with the SOAS Library Special Collections under Heidi, Alex and Ed, I was given the opportunity to create a digital exhibition. Selecting materials from the SOAS digital library, researching, and finally displaying them on a digital exhibition platform.

This was an incredibly valuable experience for me as a second-year history student with a budding interest in archiving and curating. Through archival work and curation, the notion that history is purely theoretical is uprooted. We are forced to engage with the artefacts that make up history itself, closing the gaps of time and space.

My internship at the SOAS Library

At the beginning of the internship, I was introduced to the SOAS Library Special Collections. I was given a tour of the SOAS archives and taught how to use the digital library. I was in awe of how vast the collections were and how they spanned the globe. I had the opportunity to select my own materials from the archive and request to digitise artefacts that weren’t already online.

After selecting my materials and writing my exhibition proposal, I was taught how to create IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework) image APIs. This sounds very complicated but is actually quite straightforward! It was a matter of uploading my materials onto archive.org and then using the image identifier to create a link that could then be uploaded onto the digital exhibition platform. Although this was daunting at first, it showed me what goes into creating digital exhibitions, demystifying the process.

I had the opportunity to select my own materials from the archive and request to digitise artefacts that weren’t already online.

When writing my exhibition labels, I was encouraged to express my own positionality. This freedom was especially motivating as I knew I wanted to develop my interests in South Asian history through the lenses of decoloniality, gender, and caste. This ability to be critical of the materials I selected, particularly their provenance, allowed me to begin to dismantle the dominant narratives held within them. I, therefore, got to appreciate the global nature of the archives whilst also scrutinising how the objects came into being.

My exhibition focused on reclaiming South Asian identity from the colonial gaze

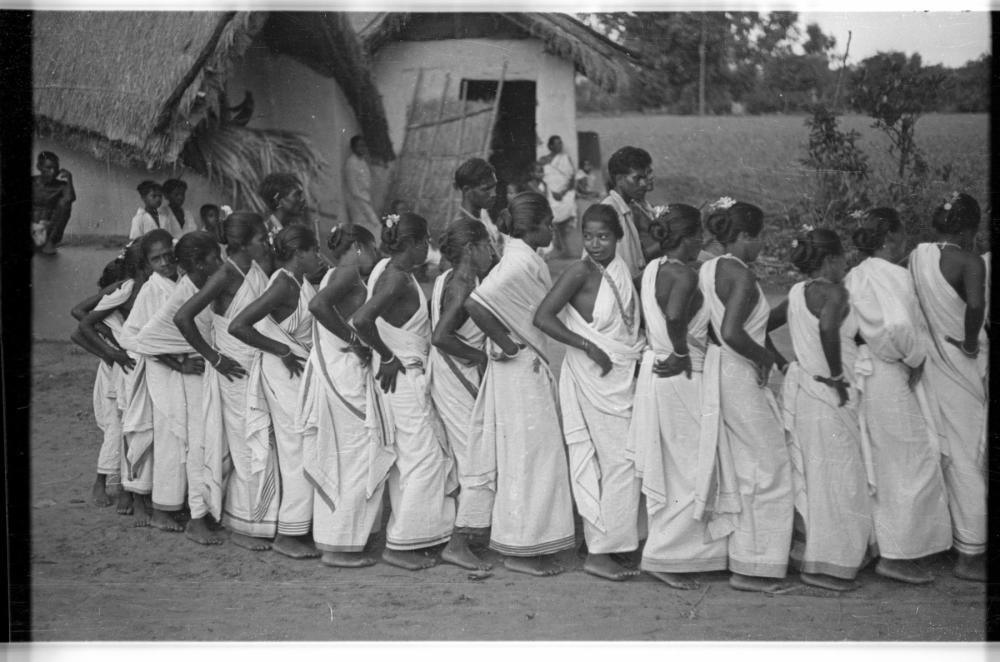

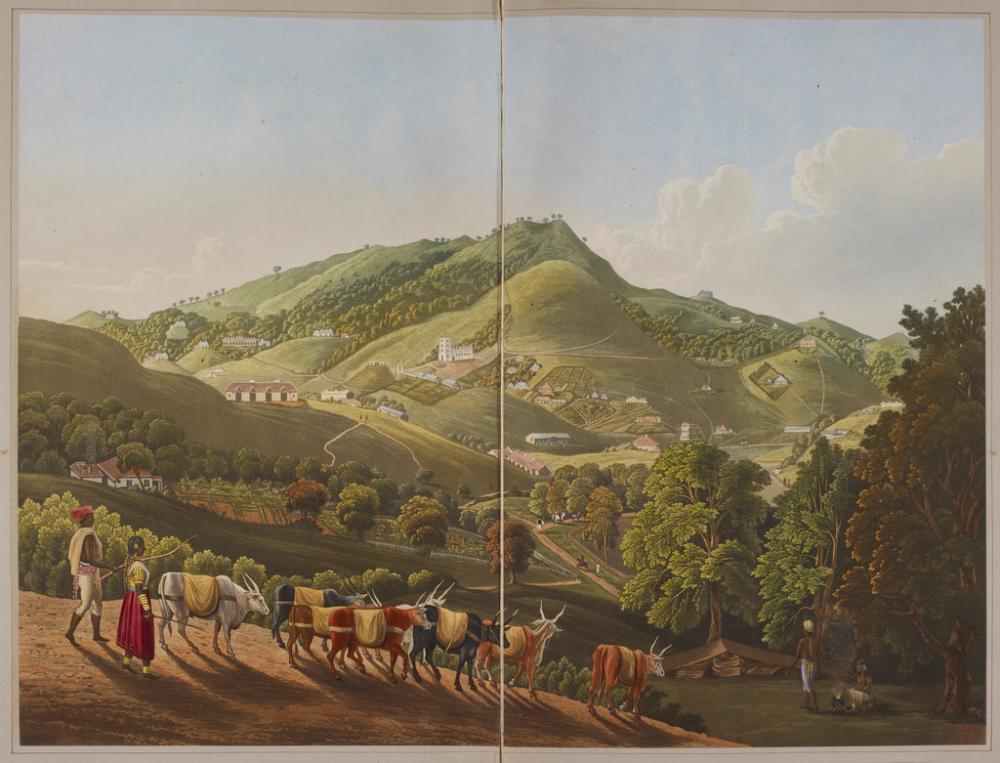

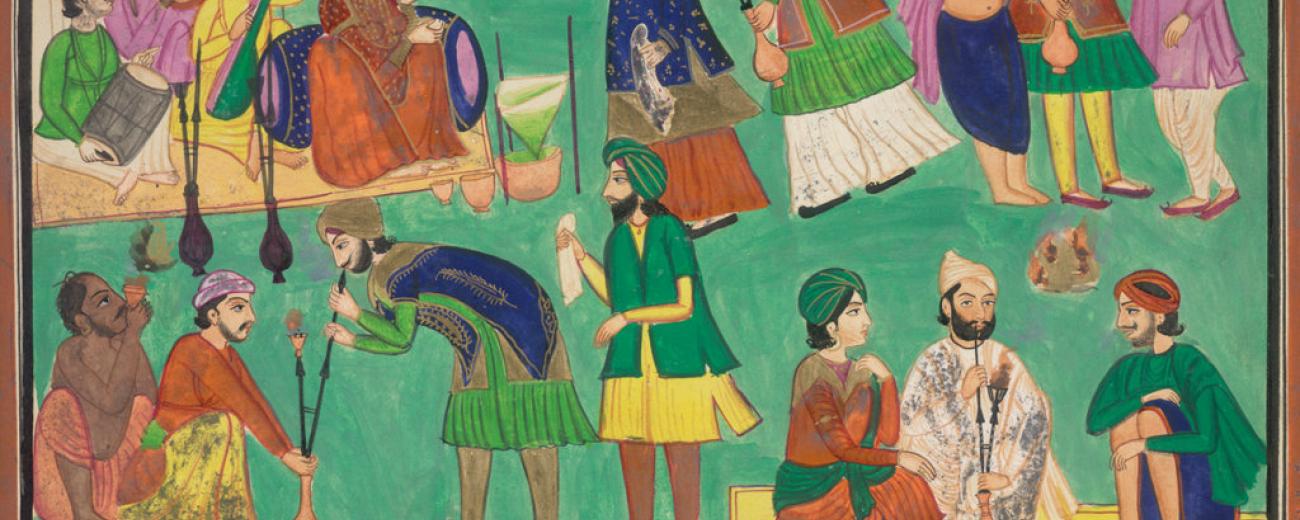

The idea of the ‘colonial gaze’ stuck out to me when finding masses of colonial ethnographic photography of South Asian communities. I, therefore, chose to centre my exhibition on retrieving South Asian identity from this gaze. I mainly chose to depict this through art and photography created during and in the aftermath of the colonial period in India. I found it interesting to highlight the role of anthropology in the construction of colonial knowledge through classification.

For instance, Company-style Paintings, shifted Indian art styles to suit European tastes. Importing new art techniques, Indian artists were commissioned to illustrate their culture as records of society or as souvenirs for British tourists. This idea of ‘record’ was central to the colonial project as it allowed it to paint an ’inferior’ image of Indian society through European intellectualism.

I also decided to finish my exhibition by showing how Indians themselves subverted the ‘colonial gaze’ by expressing their ‘deviant’ identities. For example, showcasing the work and life of Pandita Ramabai, a social reformer and feminist who stood firmly against colonial authorities and Hindu male intellectuals. By scrutinising the archives, we can disrupt the homogenous narratives that continue to perpetuate colonial ideologies.

The overall value of digital exhibitions

I thought the digital format of the exhibition was incredibly useful to display the intricacies of my artefacts. It allows users to look closer at images and objects, zooming into details that may be overlooked in a physical exhibition.

I could convey my own positionality by spotlighting features of my materials, from specific quotes in leaflets to brushstrokes in paintings. I found I could write more about my materials than in a traditional exhibition, delving deeper into their significance in relation to the colonial gaze. This allowed me to weave my own perspective into every aspect of the exhibition.

By showcasing them virtually we can expand and share objects globally, central to the duty of decolonisation which museums must undertake.

Although possessing a different ‘feel’ to physical exhibitions, I think online exhibitions can be more accessible as they allow objects to be experienced by a wider audience. Unlike a physical one, it can span time and space, being shared with a single link. Thus, not attempting to replicate physical exhibitions, I think we can use online exhibitions to explore the archives in our new digital age. By showcasing them virtually we can expand and share objects globally, central to the duty of decolonisation which museums must undertake.

My recommended reading list

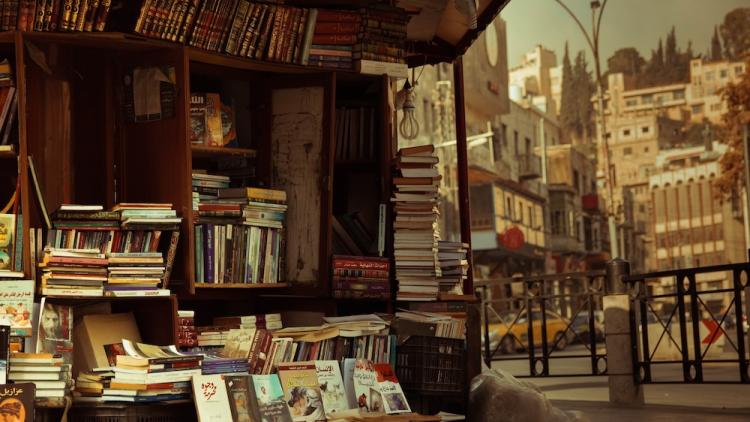

- A High-Tech Heist at the British Museum: This article shows how tech can be used to radically decolonise museums and make artefacts accessible to the public.

- Enter Sultana's Reality: This website shows how digital spaces can be used to showcase history creatively using animation.

- Radical online collections and archives: This website provides radical literature from around the world.

About the author

Sahaana Parekh is a second-year BA History student and worked as a co-creator intern at the SOAS Library Special Collections. She is interested in feminist and South Asian history through the lenses of intersectionality and decoloniality and aspires to work in archiving and curation.